47

follow @hurlinghampolo

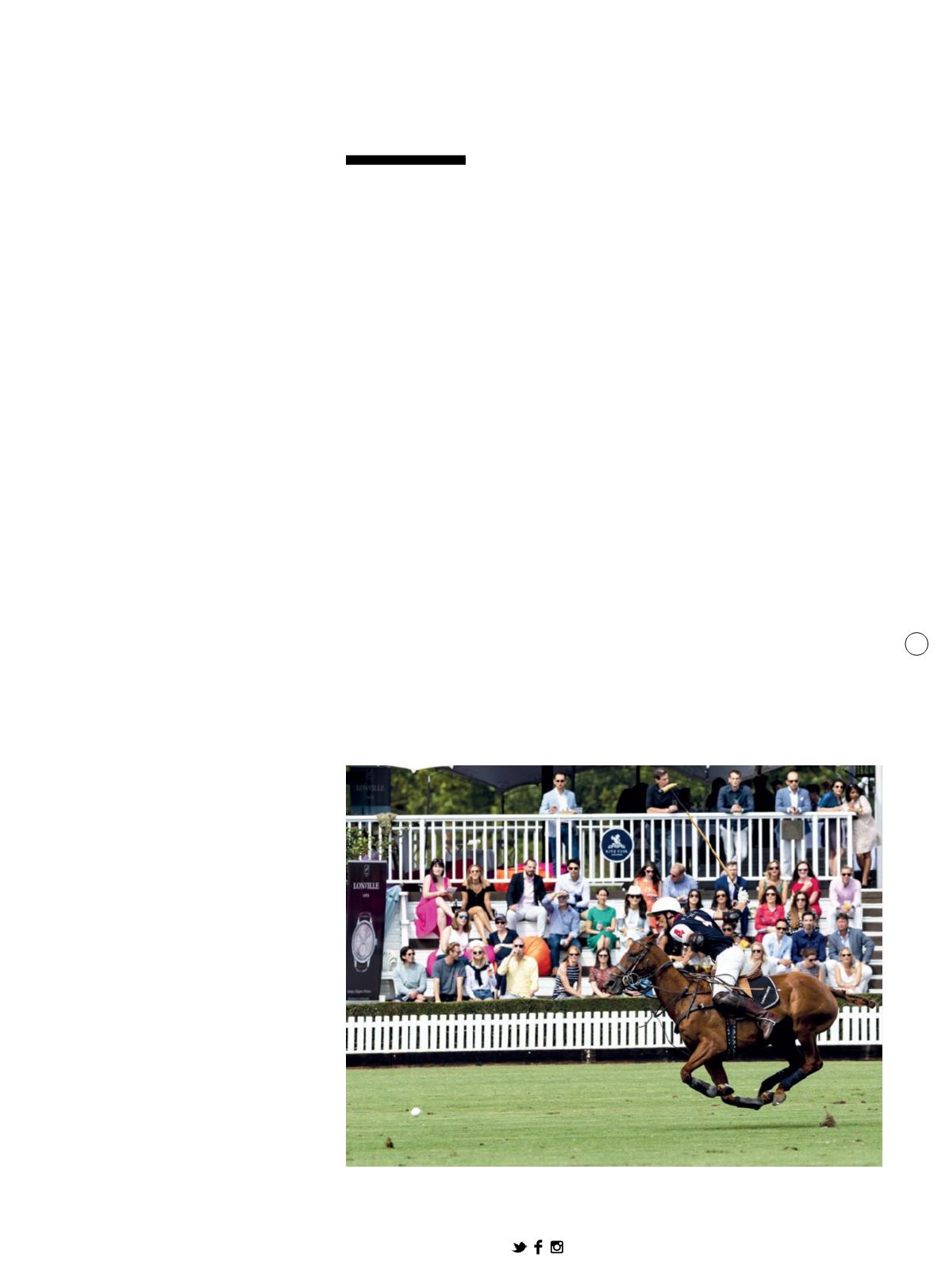

D O R S E T P O LO C LU B , R O B E R T P I P E R

T I B U S E A Q U A E C O N S E E L

E A R UMQ U AT I S U T Q U E I P I T E M

I N I E N D E V E S I G N A

There is a quiet revolution taking place on

polo fields up and down the country. No

longer the preserve of the Hooray Henry

set, polo is shedding its elitist image (not an

easy task, granted, when Prince Harry and

George Spencer-Churchill are two of the

sport’s biggest names in the UK). But with

events such as Chestertons Polo in the

Park drawing ever bigger crowds, and

charities such as Power Of Polo (

powerofpolo.

org.uk

) reaching inner-city youth, there is

a distinct feeling of change in the air.

‘The press prefers to sell polo as an

exclusive sport for royalty and celebrities,

or “Argentine demi-gods”,’ says Nathaniel

McCullagh, COO of London Alumni Polo

Club (

alumnipolo.co.uk)

, whose film

The Polo

Kid

aims to bring the sport to a wider

audience. ‘They don’t talk about the reality

of the tens of thousands of active polo

players around the world who come from

ordinary backgrounds.’

‘Books such as Jilly Cooper’s

Polo

describe

a rarefied world that you have to be born into,

or win the lottery to buy your way into. We

need to dispel these myths and get as many

people as possible to come and watch a polo

game, or better still, to participate.’

But how, or more specifically, where do

you begin? Well, as with so many things in life

(some more ill-advised than others), university

seems to be the place to start dabbling. In

fact, the Schools and Universities Polo

Association (

supa.org.uk

) lists nearly 60

participating establishments on its website.

Founded in 1991, SUPA organises and

runs national tournaments at all levels, as

well as hosting international teams at the

annual SUPA International Festival in early

July. Last year, the organisation celebrated

its 25th anniversary by launching a

programme called ‘Introduction to Polo’

comprising three to four group sessions to

encourage newcomers to take up the game.

The key thing about university polo is

that it’s open to any student and requires no

previous riding experience. Clubs take part in

friendly chukkas against other universities in

mixed teams and also compete in larger SUPA

league tournaments. Crucially, there is no

need to own your own string of ponies as The

Association of Polo Schools and Pony Hirers

(

apsph-polo.org.uk

) can rent you a ride.

‘In clubs like Alumni Polo, no one owns their

own horses,’ explains McCullagh. ‘You can

work your way up to being a really strong

amateur player – up to say, one or two goals

without owning horses, and for many players

this is enough. However, many Alumni Polo

members do, in time, go on to become

members and patrons of the larger clubs.’

So with horse ownership no longer

a barrier to entry, what’s stopping every

Tom, Dick and (non-royal) Harry from

joining in the sport? Cost is the answer

that comes up again and again.

As McCullagh points out, ‘When you

are learning, and for the first few years

afterwards, polo is not any more expensive

than, say, playing golf. And as a spectator

it offers incredible value for money. What

other sport allows you to watch some of the

best players and athletes in the world, in

a beautiful setting, for £5 per person? After

you have bought a couple of drinks and some

food, you get a full afternoon’s entertainment

for about £25 – much cheaper than going to

watch a football game. You can also bring

a picnic to make it even cheaper.’

And if, after watching a few chukkas

with a glass of champagne in hand, you

fancy giving it a go, then many smaller clubs

around the country are more than happy to

show you the ropes.

Two hours’ drive from London,

Dorset Polo Club (

dorsetpolo.co.uk)

offers

special packages including the Polo Starter

Package, which is aimed at those who have

had a go and want to take their love of the

Y O U C A N B E C OME A S T R O N G A M AT E U R

P L AY E R W I T H O U T OWN I N G H O R S E S